One word that is tightly connected with Massive MIMO is pilot contamination. This is a phenomenon that can appear in any communication system that operates under interference, but in this post, I will describe its basic properties in Massive MIMO.

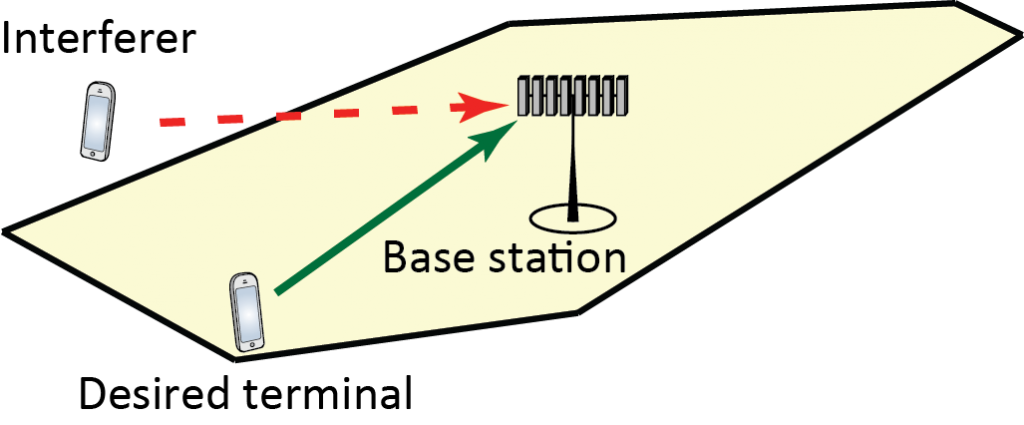

The base station wants to know the channel responses of its user terminals and these are estimated in the uplink by sending pilot signals. Each pilot signal is corrupted by inter-cell interference and noise when received at the base station. For example, consider the scenario illustrated below where two terminals are transmitting simultaneously, so that the base station receives a superposition of their signals—that is, the desired pilot signal is contaminated.

When estimating the channel from the desired terminal, the base station cannot easily separate the signals from the two terminals. This has two key implications:

First, the interfering signal acts as colored noise that reduces the channel estimation accuracy.

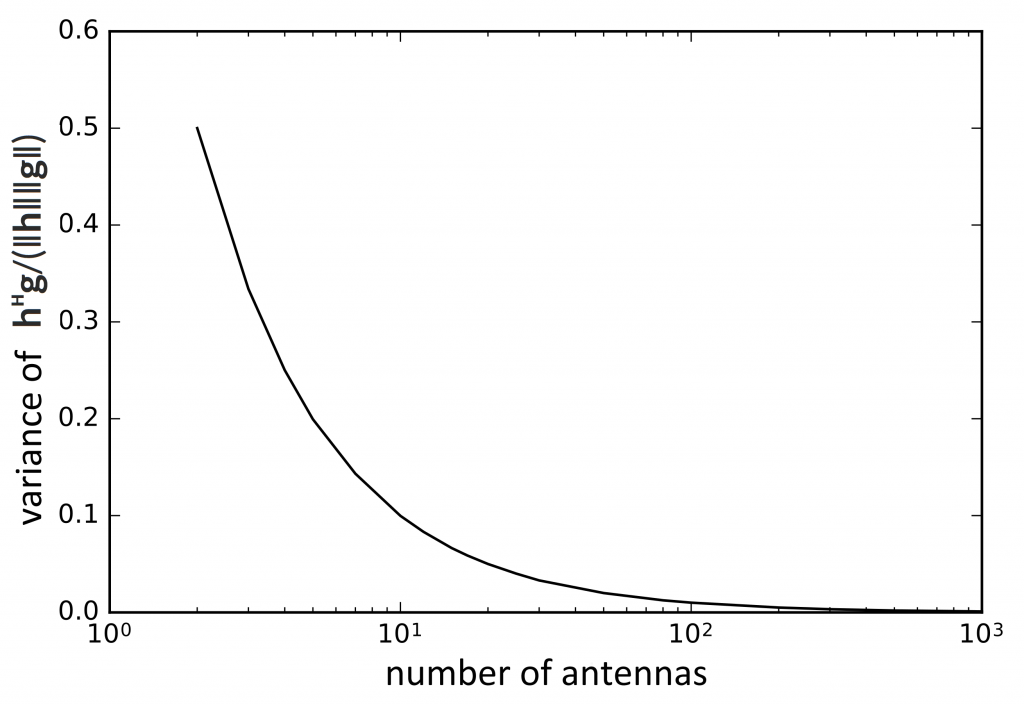

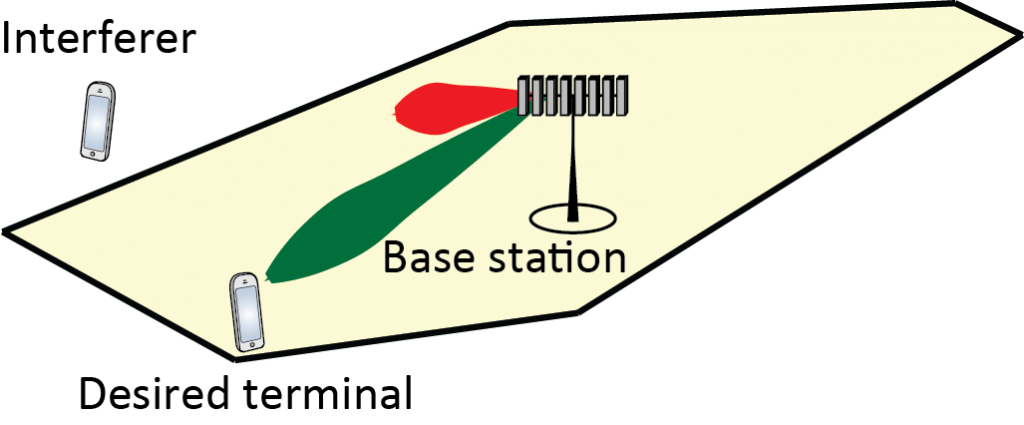

Second, the base station unintentionally estimates a superposition of the channel from the desired terminal and from the interferer. Later, the desired terminal sends payload data and the base station wishes to coherently combine the received signal, using the channel estimate. It will then unintentionally and coherently combine part of the interfering signal as well. This is particularly poisonous when the base station has M antennas, since the array gain from the receive combining increases both the signal power and the interference power proportionally to M. Similarly, when the base station transmits a beamformed downlink signal towards its terminal, it will unintentionally direct some of the signal towards to interferer. This is illustrated below.

In the academic literature, pilot contamination is often studied under the assumption that the interfering terminal sends the same pilot signal as the desired terminal, but in practice any non-orthogonal interfering signal will cause the two effects described above.