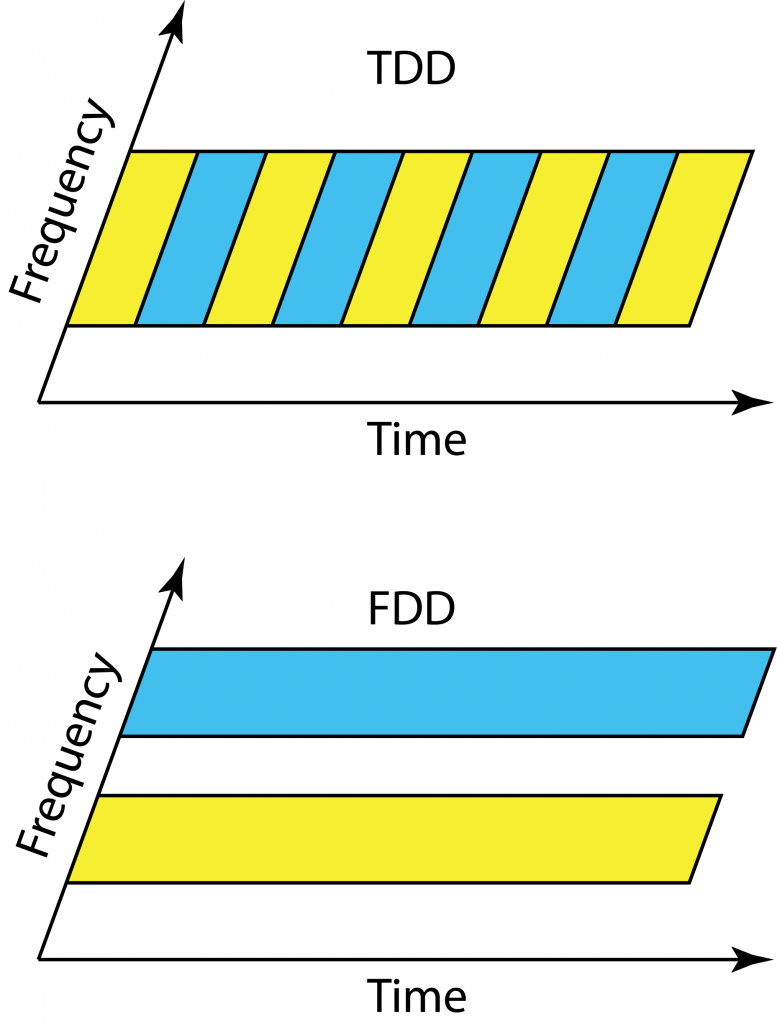

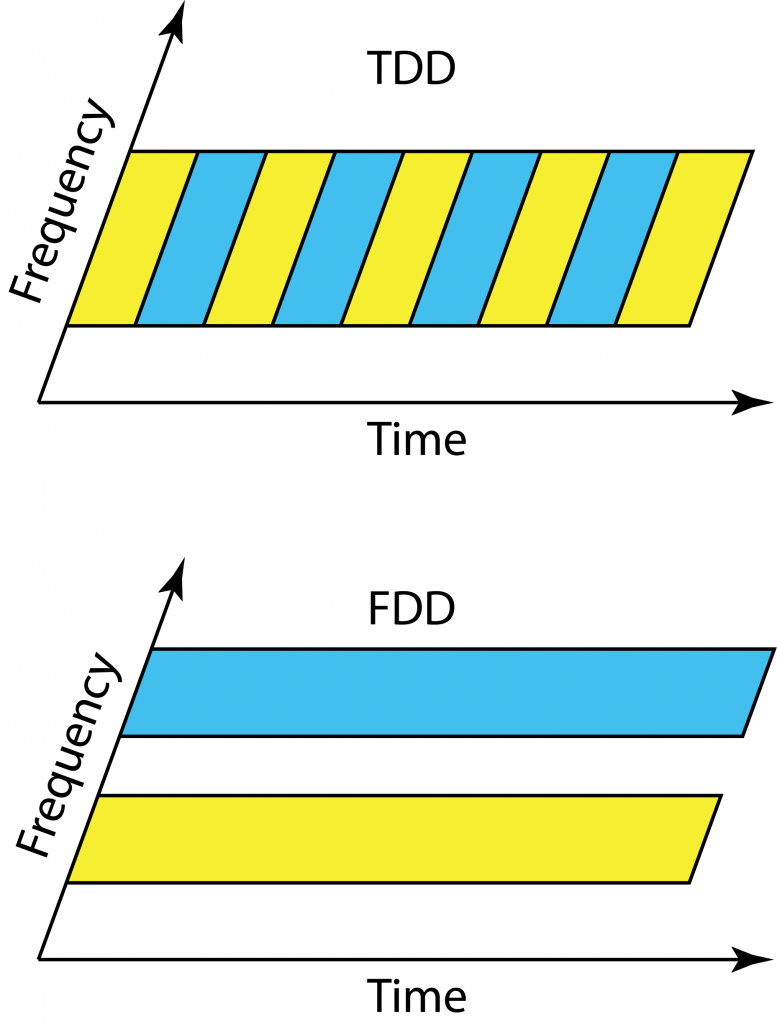

LTE was designed to work equally well in time-division duplex (TDD) and frequency division duplex (FDD) mode, so that operators could choose their mode of operation depending on their spectrum licenses. In contrast, Massive MIMO clearly works at its best in TDD, since the pilot overhead is prohibitive in FDD (even if there are some potential solutions that partially overcome this issue).

LTE was designed to work equally well in time-division duplex (TDD) and frequency division duplex (FDD) mode, so that operators could choose their mode of operation depending on their spectrum licenses. In contrast, Massive MIMO clearly works at its best in TDD, since the pilot overhead is prohibitive in FDD (even if there are some potential solutions that partially overcome this issue).

Clearly, we will see a larger focus on TDD in future networks, but there are some traditional disadvantages with TDD that we need to bear in mind when designing these networks. I describe the three main ones below.

Link budget

Even if we allocate the same amount of time-frequency resources to uplink and downlink in TDD and FDD operation, there is an important difference. We transmit over half the bandwidth all the time in FDD, while we transmit over the whole bandwidth half of the time in TDD. Since the power amplifier is only active half of the time, if the peak power is the same, the average radiated power is effectively cut in half. This means that the SNR is 3 dB lower in TDD than in FDD, when transmitting at maximum peak power.

Massive MIMO systems are generally interference-limited and uses power control to assign a reduced transmit power to most users, thus the impact of the 3 dB SNR loss at maximum peak power is immaterial in many cases. However, there will always be some unfortunate low-SNR users (e.g., at the cell edge) that would like to communicate at maximum peak power in both uplink and downlink, and therefore suffer from the 3 dB SNR loss. If these users are still able to connect to the base station, the beamforming gain provided by Massive MIMO will probably more than compensate for the loss in link budget as compared single-antenna systems. One can discuss if it should be the peak power or average radiated power that is constrained in practice.

Guard period

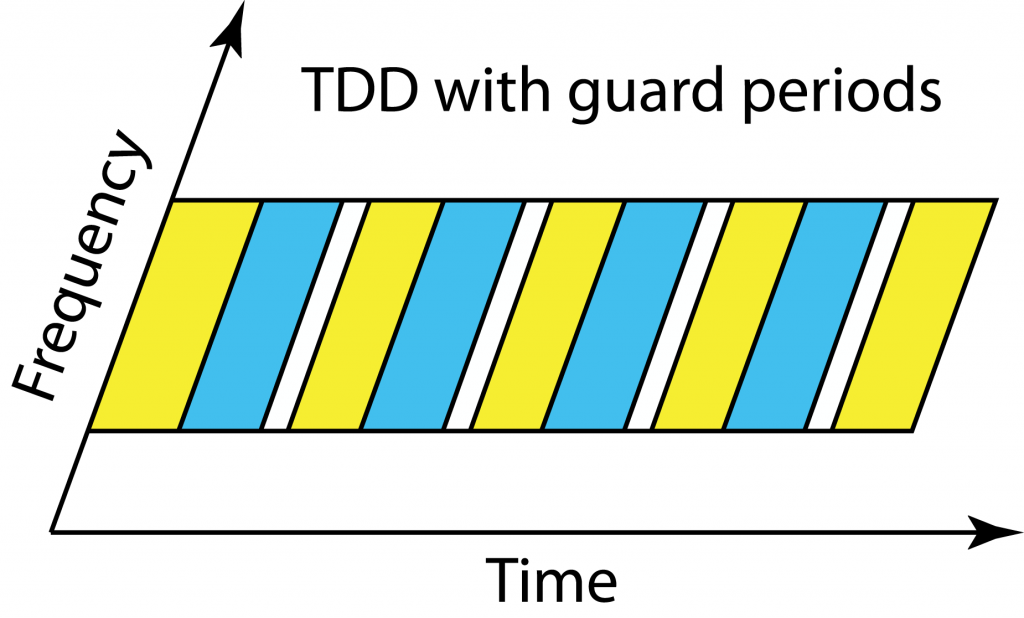

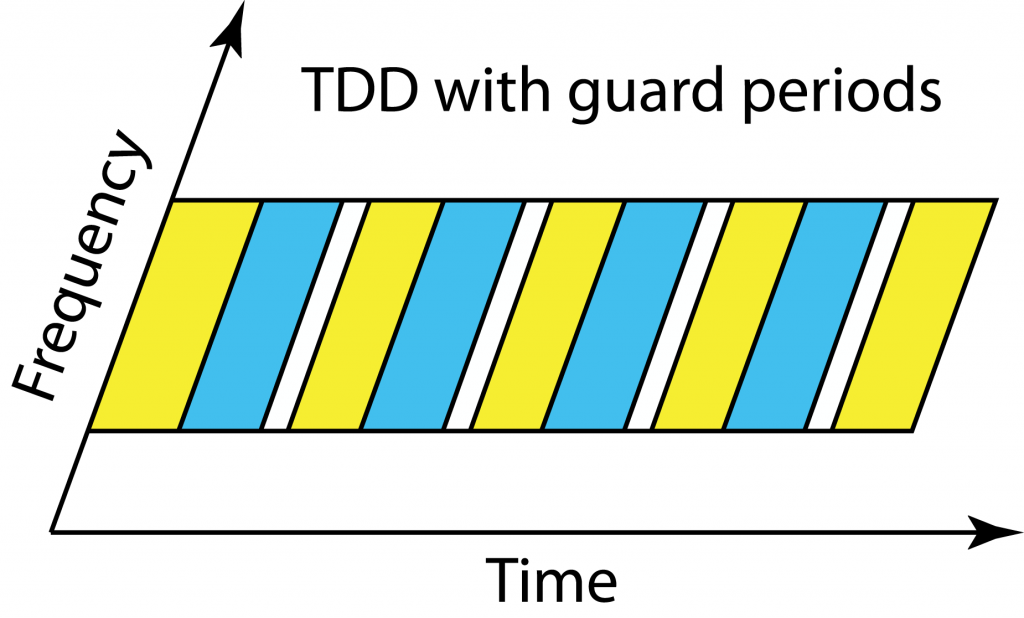

Everyone in the cell should operate in uplink and downlink mode at the same time in TDD. Since the users are at different distances from the base station and have different delay spreads, they will receive the end of the downlink transmission block at different time instances. If a cell center user starts to transmit in the uplink immediately after receiving the full downlink block, then users at the cell edge will receive a combination of the delayed downlink transmission and the cell center users’ uplink transmissions. To avoid such uplink-downlink interference, there is a guard period in TDD so that all users wait with uplink transmission until the outmost users are done with the downlink.

Everyone in the cell should operate in uplink and downlink mode at the same time in TDD. Since the users are at different distances from the base station and have different delay spreads, they will receive the end of the downlink transmission block at different time instances. If a cell center user starts to transmit in the uplink immediately after receiving the full downlink block, then users at the cell edge will receive a combination of the delayed downlink transmission and the cell center users’ uplink transmissions. To avoid such uplink-downlink interference, there is a guard period in TDD so that all users wait with uplink transmission until the outmost users are done with the downlink.

In fact, the base station gives every user a timing bias to make sure that when the uplink commences, the users’ uplink signals are received in a time-synchronized fashion at the base station. Therefore, the outmost users will start transmitting in the uplink before the cell center users. Thanks to this feature, the largest guard period is needed when switching from downlink to uplink, while the uplink to downlink switching period can be short. This is positive for Massive MIMO operation since we want to use uplink CSI in the next downlink block, but not the other way around.

The guard period in TDD must become larger when the cell size increases, meaning that a larger fraction of the transmission resources disappears. Since no guard periods are needed in FDD, the largest benefits of TDD will be seen in urban scenarios where the macro cells have a radius of a few hundred meters and the delay spread is short.

Inter-cell synchronization

We want to avoid interference between uplink and downlink within a cell and the same thing applies for the inter-cell interference. The base stations in different cells should be fairly time-synchronized so that the uplink and downlink take place at the same time; otherwise, it might happen that a cell-edge user receives a downlink signal from its own base station and is interfered by the uplink transmission from a neighboring user that connects to another base station.

This can also be an issue between telecom operators that use neighboring frequency bands. There are strict regulations on the permitted out-of-band radiation, but the out-of-band interference can anyway be larger than the desired inband signal if the interferer is very close to the receiving inband user. Hence, it is preferred that the telecom operators are also synchronizing their switching between uplink and downlink.

Summary

Massive MIMO will bring great gains in spectral efficiency in future cellular networks, but we should not forget about the traditional disadvantages of TDD operation: 3 dB loss in SNR at peak power transmission, larger guard periods in larger cells, and time synchronization between neighboring base stations.

I wrote

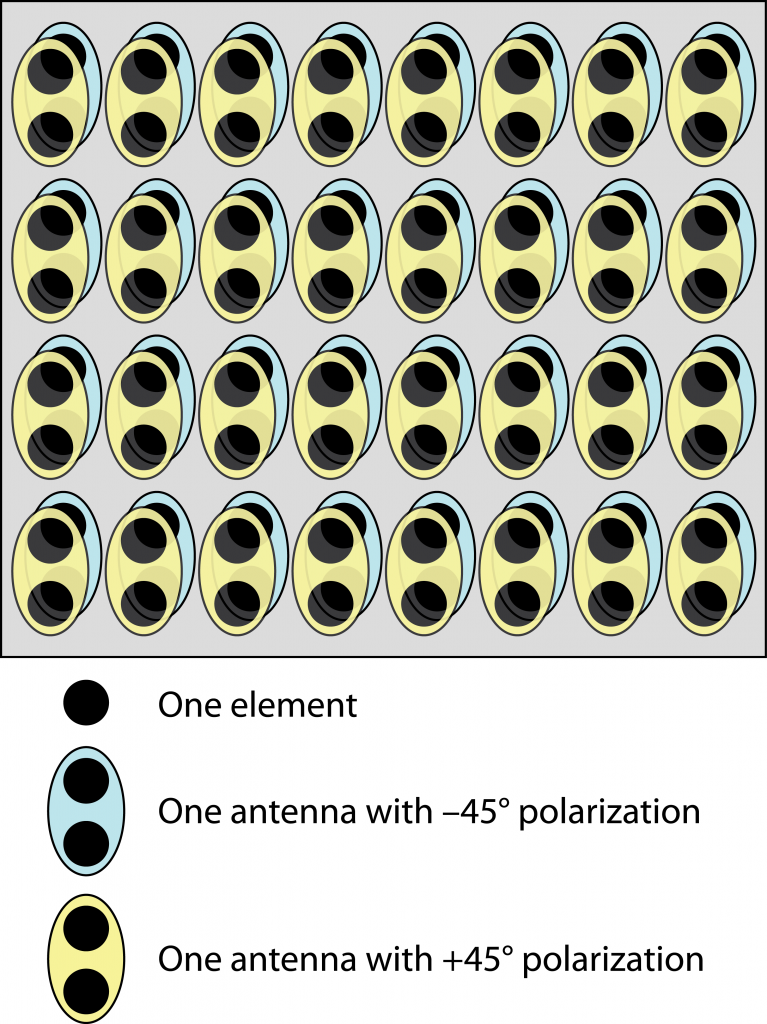

I wrote  So how are the 128 elements mapped to 64 antennas (RF chains)? This is done by taking

So how are the 128 elements mapped to 64 antennas (RF chains)? This is done by taking  LTE was designed to work equally well in

LTE was designed to work equally well in  Everyone in the cell should operate in uplink and downlink mode at the same time in TDD. Since the users are at different distances from the base station and have different delay spreads, they will receive the end of the downlink transmission block at different time instances. If a cell center user starts to transmit in the uplink immediately after receiving the full downlink block, then users at the cell edge will receive a combination of the delayed downlink transmission and the cell center users’ uplink transmissions. To avoid such uplink-downlink interference, there is a guard period in TDD so that all users wait with uplink transmission until the outmost users are done with the downlink.

Everyone in the cell should operate in uplink and downlink mode at the same time in TDD. Since the users are at different distances from the base station and have different delay spreads, they will receive the end of the downlink transmission block at different time instances. If a cell center user starts to transmit in the uplink immediately after receiving the full downlink block, then users at the cell edge will receive a combination of the delayed downlink transmission and the cell center users’ uplink transmissions. To avoid such uplink-downlink interference, there is a guard period in TDD so that all users wait with uplink transmission until the outmost users are done with the downlink.