I found an interesting news article by Reily Gregson where he is interviewing Martin Cooper, who is considered the father of the handheld cell phone. Cooper is talking about spatial division multiple access, the early name of the multi-user MIMO technology, and how “computers weren’t powerful enough to operate it” at the time it was invented at his startup-company ArrayComm.

Cooper points out that “Today we spray energy in all directions. Why not aim it directly?” He then provides three examples of why multi-user MIMO solves important practical problems:

“First, deploying cellular and derivative technologies is costly. Second, the quality of wireless communicating must be comparable or better than that of wireline in order to compete with wireline, said Cooper. And as spectrum is finite, technology must work toward greater efficiency.”

Furthermore, he says that ArrayComm’s multi-user MIMO solution “requires fewer base stations, which cuts costs. The technology also is adaptive, which simplifies network design and reduces site acquisition and installation costs.”

By the way, did I forgot to say that this interview is from 1996…?

I explained in a previous blog post why the efforts to commercialize multi-user MIMO in the nineties were not as successful as Cooper and others might have hoped for. Now, more than 20 years later, we are about to witness a large-scale deployment of 5G technology, in which MIMO is a key component. The industry has hopefully learned from the negative past experiences when Massive MIMO is now being deployed in commercial networks. One thing we know for sure is that computational complexity is not a problem anymore.

I wrote

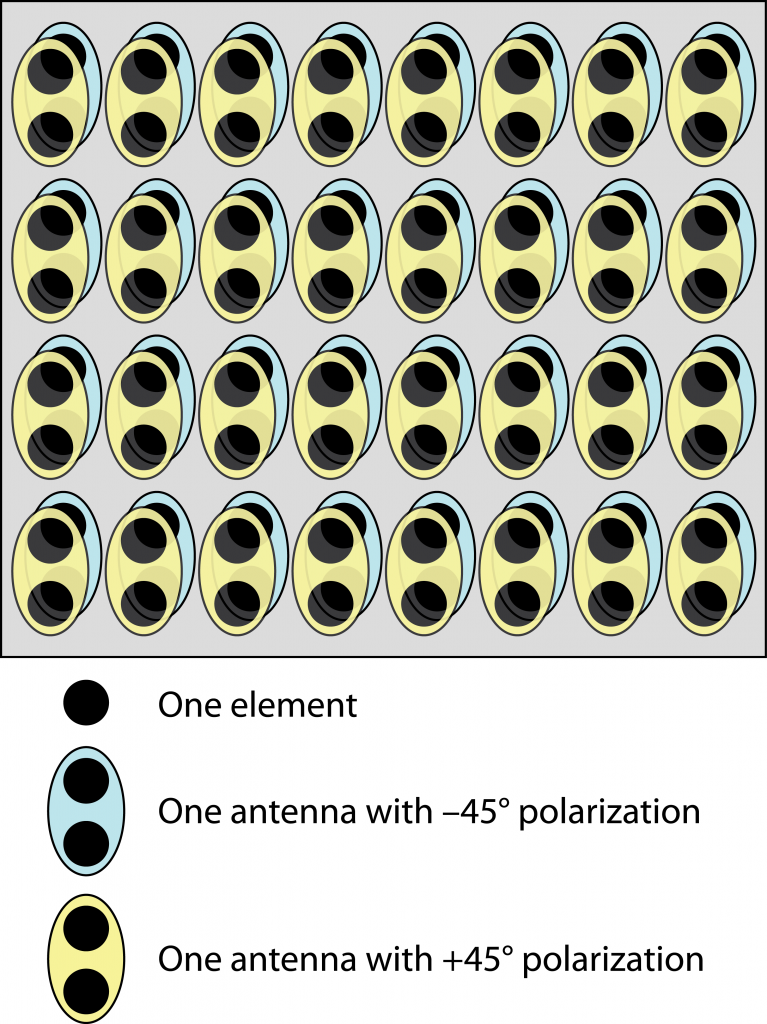

I wrote  So how are the 128 elements mapped to 64 antennas (RF chains)? This is done by taking

So how are the 128 elements mapped to 64 antennas (RF chains)? This is done by taking