The main selling point of millimeter-wave communications is the abundant bandwidth available in such frequency bands; for example, 2 GHz of bandwidth instead of 20 MHz as in conventional cellular networks. The underlying argument is that the use of much wider bandwidths immediately leads to much higher capacities, in terms of bit/s, but the reality is not that simple.

To look into this, consider a communication system operating over a bandwidth of ![]() Hz. By assuming an additive white Gaussian noise channel, the capacity becomes

Hz. By assuming an additive white Gaussian noise channel, the capacity becomes

![]()

where ![]() W is the transmit power,

W is the transmit power, ![]() is the channel gain, and

is the channel gain, and ![]() W/Hz is the power spectral density of the noise. The term

W/Hz is the power spectral density of the noise. The term ![]() inside the logarithm is referred to as the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

inside the logarithm is referred to as the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

Since the bandwidth ![]() appears in front of the logarithm, it might seem that the capacity grows linearly with the bandwidth. This is not the case since also the noise term

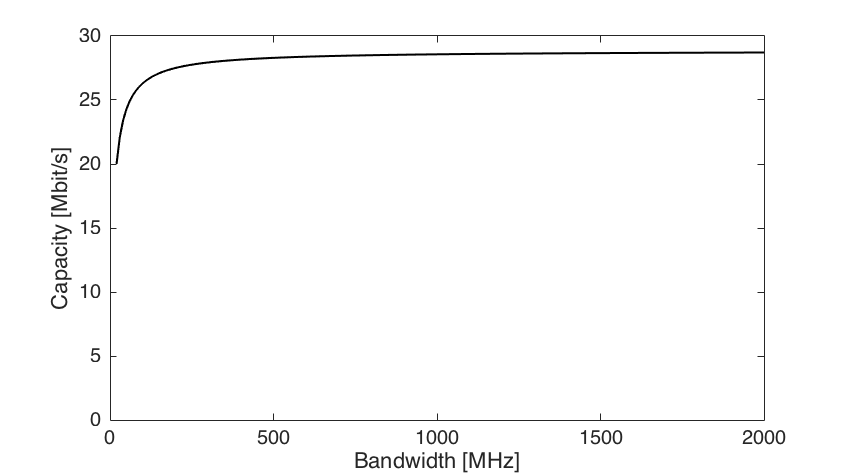

appears in front of the logarithm, it might seem that the capacity grows linearly with the bandwidth. This is not the case since also the noise term ![]() in the SNR also grows linearly with the bandwidth. This fact is illustrated by Figure 1 below, where we consider a system that achieves an SNR of 0 dB at a reference bandwidth of 20 MHz. As we increase the bandwidth towards 2 GHz, the capacity grows only modestly. Despite the 100 times more bandwidth, the capacity only improves by

in the SNR also grows linearly with the bandwidth. This fact is illustrated by Figure 1 below, where we consider a system that achieves an SNR of 0 dB at a reference bandwidth of 20 MHz. As we increase the bandwidth towards 2 GHz, the capacity grows only modestly. Despite the 100 times more bandwidth, the capacity only improves by ![]() , which is far from the

, which is far from the ![]() that a linear increase would give.

that a linear increase would give.

The reason for this modest capacity growth is the fact that the SNR reduces inversely proportional to the bandwidth. One can show that

![]()

The convergence to this limit is seen in Figure 1 and is relatively fast since ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

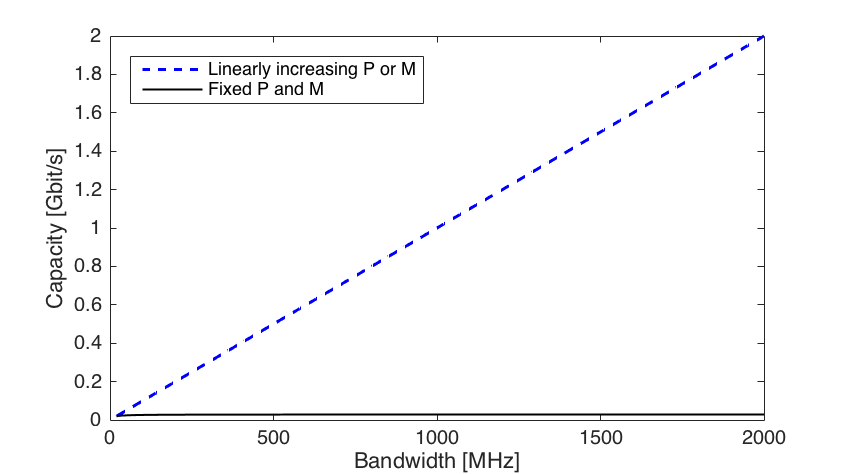

To achieve a linear capacity growth, we need to keep the SNR ![]() fixed as the bandwidth increases. This can be achieved by increasing the transmit power

fixed as the bandwidth increases. This can be achieved by increasing the transmit power ![]() proportionally to the bandwidth, which entails using

proportionally to the bandwidth, which entails using ![]() more power when operating over a

more power when operating over a ![]() wider bandwidth. This might not be desirable in practice, at least not for battery-powered devices.

wider bandwidth. This might not be desirable in practice, at least not for battery-powered devices.

An alternative is to use beamforming to improve the channel gain. In a Massive MIMO system, the effective channel gain is ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the number of antennas and

is the number of antennas and ![]() is the gain of a single-antenna channel. Hence, we can increase the number of antennas proportionally to the bandwidth to keep the SNR fixed.

is the gain of a single-antenna channel. Hence, we can increase the number of antennas proportionally to the bandwidth to keep the SNR fixed.

Figure 2 considers the same setup as in Figure 1, but now we also let either the transmit power or the number of antennas grow proportionally to the bandwidth. In both cases, we achieve a capacity that grows proportionally to the bandwidth, as we initially hoped for.

In conclusion, to make efficient use of more bandwidth we require more transmit power or more antennas at the transmitter and/or receiver. It is worth noting that these requirements are purely due to the increase in bandwidth. In addition, for any given bandwidth, the operation at millimeter-wave frequencies requires much more transmit power and/or more antennas (e.g., additional constant-gain antennas or one constant-aperture antenna) just to achieve the same SNR as in a system operating at conventional frequencies below 5 GHz.

What is the impact on the energy efficiency by increasing the number of antennas, proportionally to the bandwidth, to have a linear capacity growth?

If we define energy efficiency as “capacity / power”, we need an accurate power consumption model that includes both transmit power and circuit power. In particular, it must allow us to modify both the bandwidth B and the number of antennas M. I am not sure how such a model would look like that, but I guess it will contain a term that grows proportionally to B*M. If that is the case, the energy efficiency might increase in the beginning when we increase the bandwidth, but eventually it will reach a maximum value and go towards zero as we further increase the bandwidth (and number of antennas).