Channel estimation is critical in Massive MIMO. One can use the basic least-squares (LS) channel estimator to learn the multi-antenna channel from pilot signals, but if one has prior information about the channel’s properties, that can be used to improve the estimation quality. For example, if one knows the average channel gain, the linear minimum mean-squared error (LMMSE) estimator can be used, as in most of the literature on Massive MIMO.

There are many attempts to exploit further channel properties, in particularly channel sparsity is commonly assumed in the academic literature. I have recently received several questions about this topic, so I will take the opportunity to give a detailed answer. In particular, this blog post discusses temporal and spatial sparsity.

Temporal sparsity

This means that the channel’s impulse response contains one or several pulses with zeros in between. These pulses could represent different paths, in a multipath environment, which are characterized by non-overlapping time delays. This does not happen in a rich scattering environment with many diffuse scatterers having overlapping delays, but it could happen in mmWave bands where there are only a few reflected paths.

If one knows that the channel has temporal sparsity, one can utilize such knowledge in the estimator to determine when the pulses arrive and what properties (e.g., phase and amplitude) each one has. However, several hardware-related conditions need to be satisfied. Firstly, the sampling rate must be sufficiently high so that the pulses can be temporally resolved without being smeared together by aliasing. Secondly, the receiver filter has an impulse response that spreads signals out over time, and this must not remove the sparsity.

Spatial sparsity

This means that the multipath channel between the transmitter and receiver only involves paths in a limited subset of all angular directions. If these directions are known a priori, it can be utilized in the channel estimation to only estimate the properties (e.g., phase and amplitude) in those directions. One way to determine the existence of spatial sparsity is by computing a spatial correlation matrix of the channel and analyze its eigenvalues. Each eigenvalue represents the average squared amplitude in one set of angular directions, thus spatial sparsity would lead to some of the eigenvalues being zero.

Just as for temporal sparsity, it is not necessary that spatial sparsity can be utilized even if it physically exists. The antenna array must be sufficiently large (in terms of aperture and number of antennas) to differentiate between directions with signals and directions without signals. If the angular distance between the channel paths is smaller than the beamwidth of the array, it will smear out the paths over many angles. The following example shows that Massive MIMO is not a guarantee for utilizing spatial sparsity.

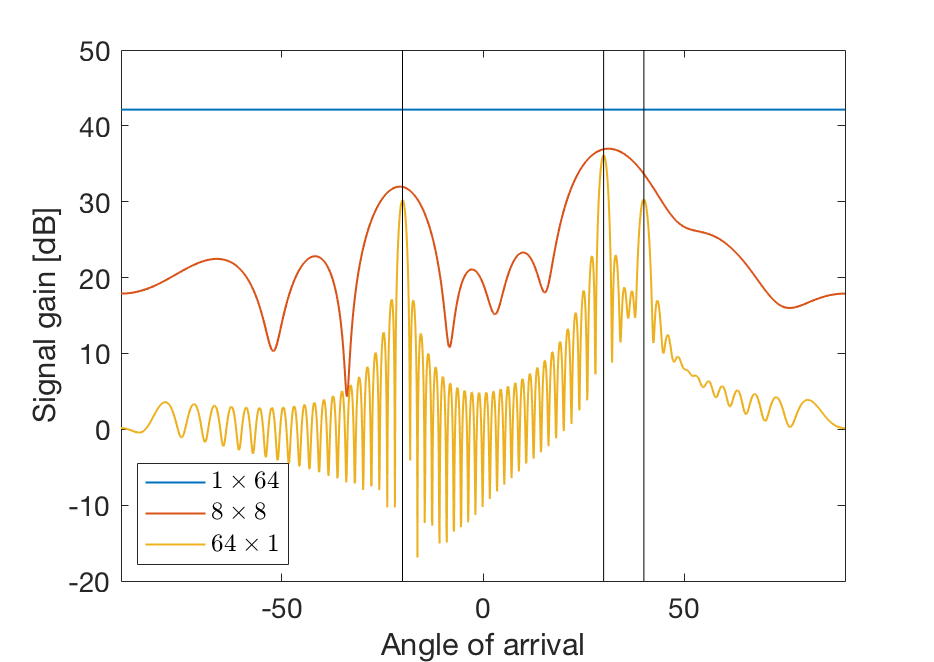

The figure below considers a 64-antenna scenario where the received signal contains only three paths, having azimuth angles -20°, +30° and +40° and a common elevation angle of 0°. If the 64 antennas are vertically stacked (denoted 1 x 64), the signal gain seems to be the same from all azimuth directions, so the sparsity cannot be observed at all. If the 64 antennas are horizontally stacked (denoted 64 x 1), the signal gain has distinct peaks at the angles of the three paths, but there are also ripples that could have hidden other paths. A more common 64-antenna configuration is a 8 x 8 planar array, for which only two peaks are visible. The paths 30° and 40° are lumped together due to the limited resolution of the array.

In addition to have a sufficiently high spatial resolution, a phase-calibrated array might be needed to make use of sparsity, since random phase differences between the antennas could destroy the structure.

Do we need sparsity?

There is no doubt that temporal and spatial sparsity exist, but not every channel will have it. Moreover, the transceiver hardware will destroy the sparsity unless a series of conditions are satisfied. That is why one should not build a wireless technology that requires channel sparsity because then it might not function properly for many of the users. Sparsity is rather something to utilize to improve the channel estimation in certain special cases.

TDD-reciprocity based Massive MIMO, as proposed by Marzetta and further considered in my book Massive MIMO networks, does not require channel sparsity. However, sparsity can be utilized as an add-on when available. In contrast, there are many FDD-based frameworks that require channel sparsity to function properly.

Reproduce the results: The code that was used to produce the plot can be downloaded from my GitHub.