When I went to high school in Sweden, some of my friends stayed up very late at night (due to the time difference) to watch the Super Bowl; the annual championship in the American football league. This game is generally not a big thing in Sweden, but it is huge in America.

This Sunday, the Super Bowl takes place in Atlanta and one million people are expected to come to downtown Atlanta, to either watch the game at the stadium or root for their teams in other ways. Hence, massive flows of images and videos will be posted on social media from people located in a fairly limited area. To prepare for the game, the telecom operators have upgraded their cellular networks and taken the opportunity to market their 5G efforts.

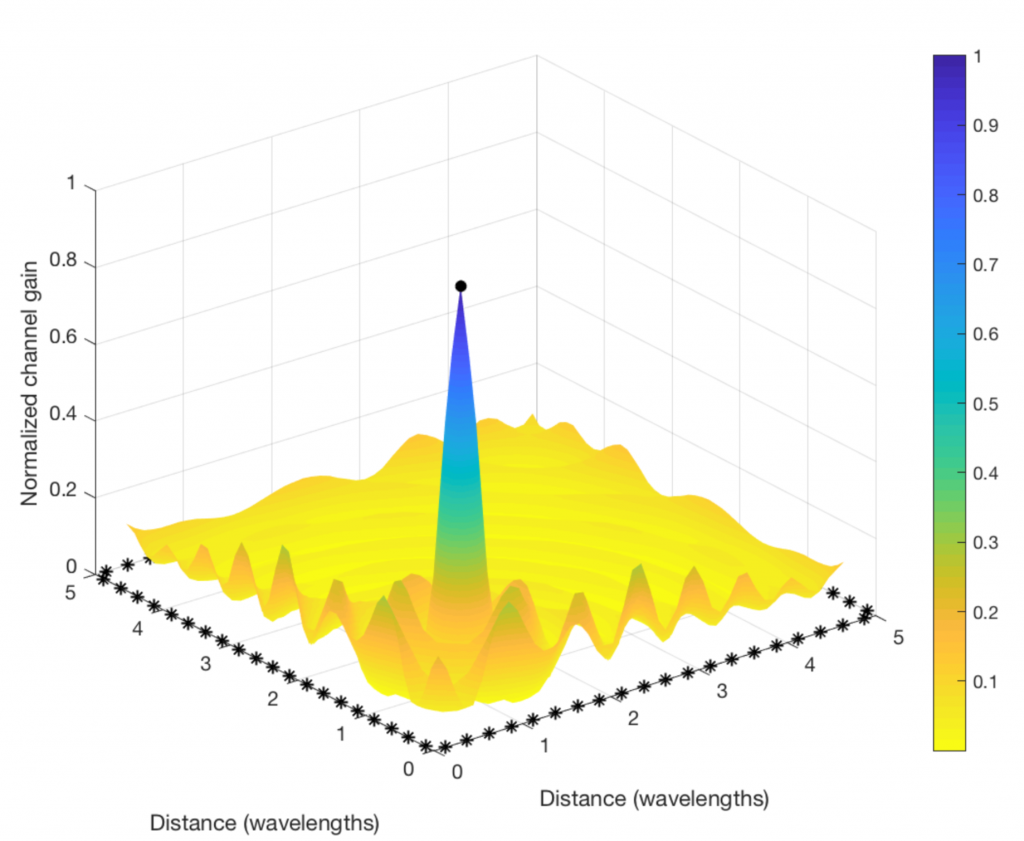

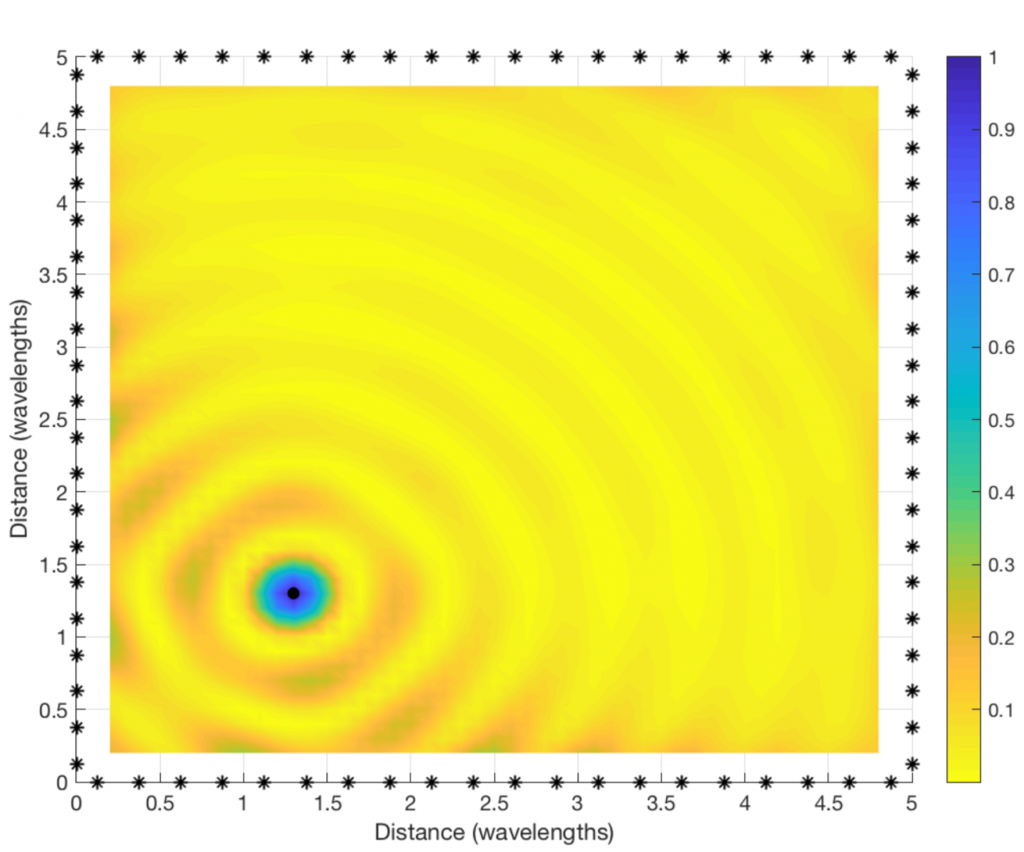

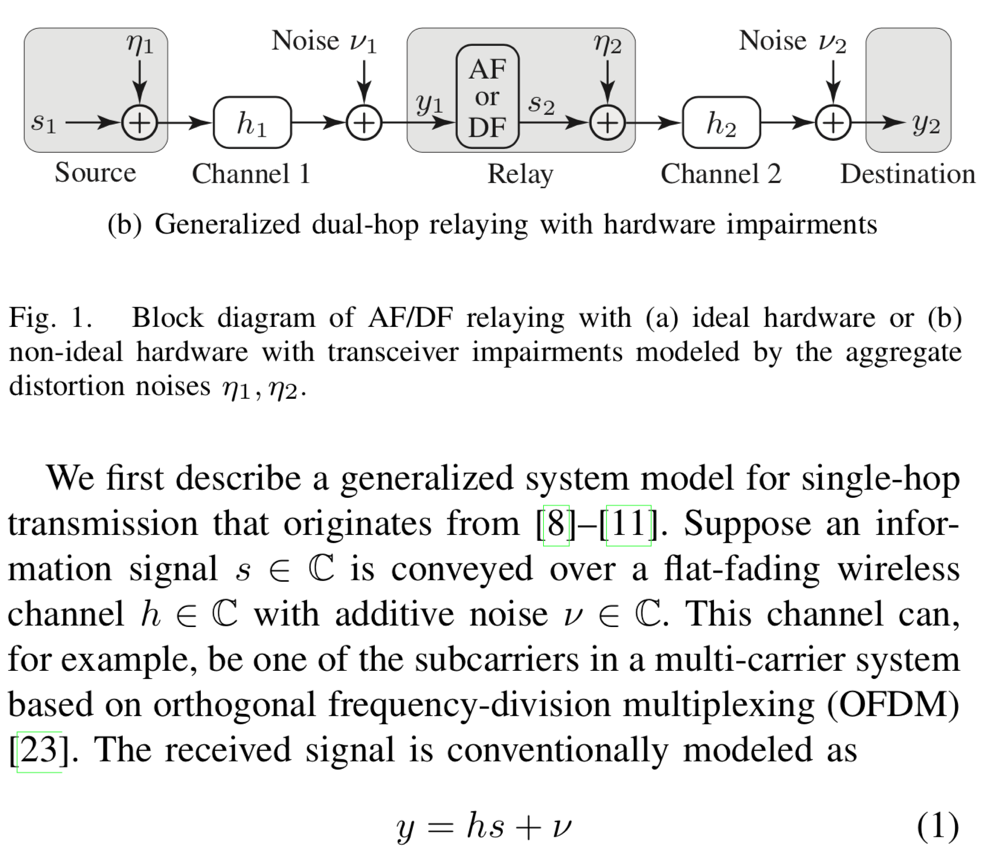

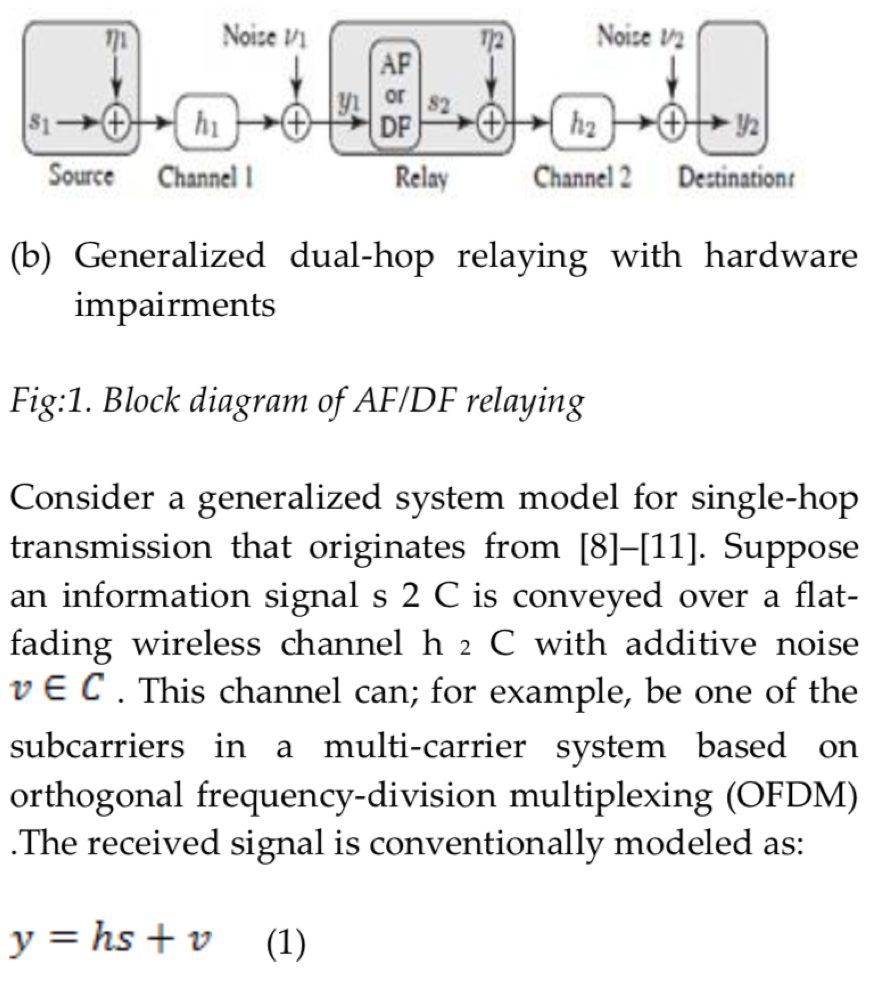

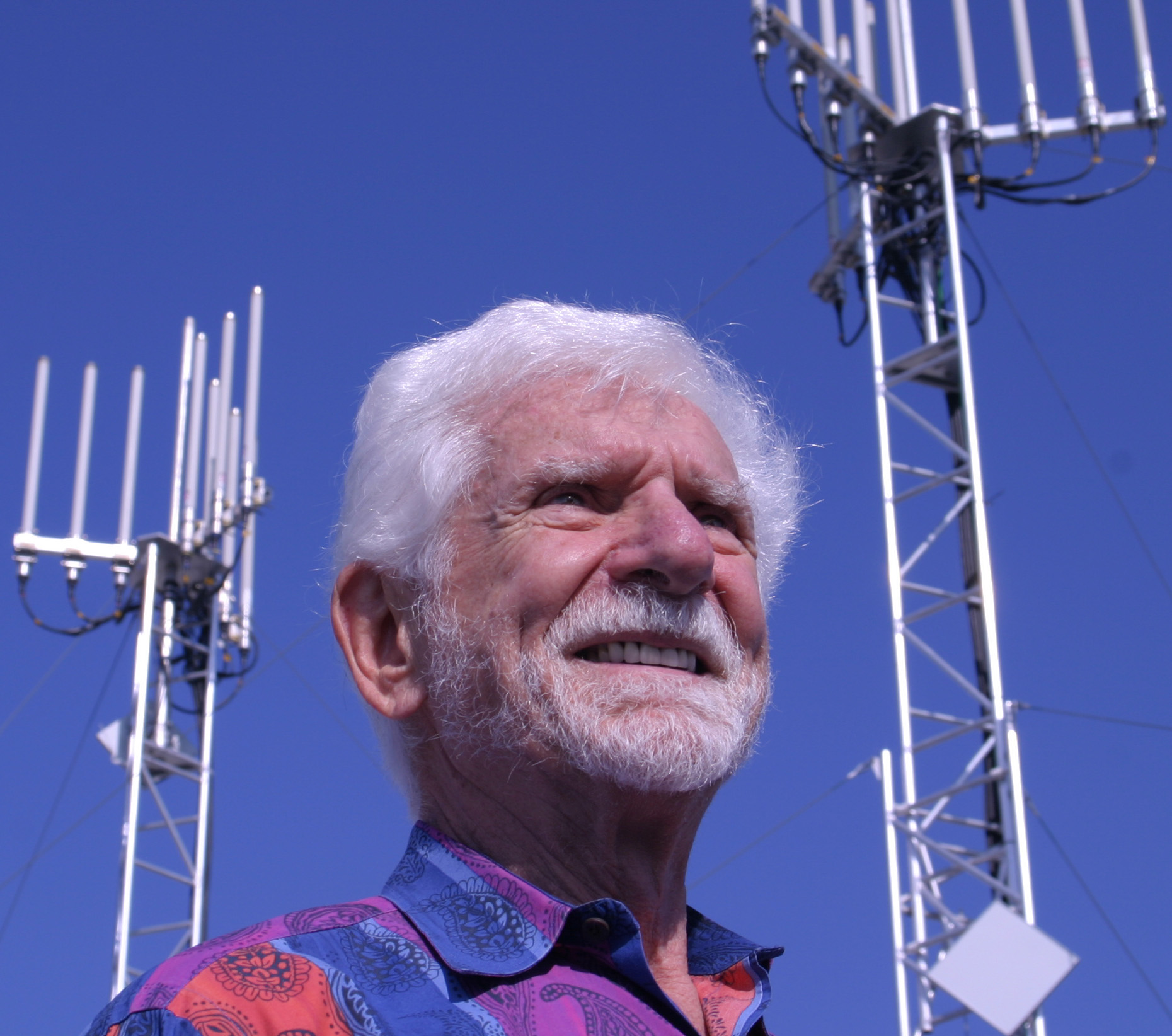

Massive MIMO in the sub-6 GHz band with 64 antennas (and 128 radiating elements) is a key technology to handle the given situation, where huge capacity can be achieved by spatially multiplexing a large number of users in the downtown. Massive MIMO is a “small box with a massive impact” Cyril Mazloum, Network Manager for Sprint in Atlanta, told Hypepotamus. This refers to the fact that the Massive MIMO equipment is, despite the naming, physically smaller than the legacy equipment it replaces. In the following video, Heather Campbell of the Sprint Network Team explains how a ten times higher capacity is achieved in the 2.5 GHz band by their Massive MIMO deployment, which I have also reported about before.

All the major cellular operators have upgraded their networks in preparation for the big game. AT&T has reportedly spent $43 million to deploy 1,500 new antennas. Verizon has installed 30 new macro sites, 300 new small cells, and upgraded the capacity of 150 existing sites. T-Mobile has reportedly boosted its network capacity by eight times. Massive MIMO and 5G are clearly one of the key technologies in all these cases.