Pilot contamination used to be seen as the key issue with the Massive MIMO technology, but thanks to a large number of scientific papers we now know fairly well how to deal with it. I outlined the main approaches to mitigate pilot contamination in a previous blog post and since then the paper Massive MIMO has unlimited capacity has also been picked up by science news channels.

Pilot contamination used to be seen as the key issue with the Massive MIMO technology, but thanks to a large number of scientific papers we now know fairly well how to deal with it. I outlined the main approaches to mitigate pilot contamination in a previous blog post and since then the paper Massive MIMO has unlimited capacity has also been picked up by science news channels.

When reading papers on pilot (de)contamination written by many different authors, I’ve noticed one recurrent issue: the mean-squared error (MSE) is used to measure the level of pilot contamination. A few papers only plot the MSE, while most papers contain multiple MSE plots and then one or two plots with bit-error-rates or achievable rates. As I will explain below, the MSE is a rather poor measure of pilot contamination since it cannot distinguish between noise and pilot contamination.

A simple example

Suppose the desired uplink signal is received with power ![]() and is disturbed by noise with power

and is disturbed by noise with power ![]() and interference from another user with power

and interference from another user with power ![]() . By varying the variable

. By varying the variable ![]() between 0 and 1 in this simple example, we can study how the performance changes when moving power from the noise to the interference, and vice versa.

between 0 and 1 in this simple example, we can study how the performance changes when moving power from the noise to the interference, and vice versa.

By following the standard approach for channel estimation based on uplink pilots (see Fundamentals of Massive MIMO), the MSE for i.i.d. Rayleigh fading channels is

![]()

which is independent of ![]() and, hence, does not care about whether the disturbance comes from noise or interference. This is rather intuitive since both the noise and interference are additive i.i.d. Gaussian random variables in this example. The important difference appears in the data transmission phase, where the noise takes a new independent realization and the interference is strongly correlated with the interference in the pilot phase, because it is the product of a new scalar signal and the same channel vector.

and, hence, does not care about whether the disturbance comes from noise or interference. This is rather intuitive since both the noise and interference are additive i.i.d. Gaussian random variables in this example. The important difference appears in the data transmission phase, where the noise takes a new independent realization and the interference is strongly correlated with the interference in the pilot phase, because it is the product of a new scalar signal and the same channel vector.

To demonstrate the important difference, suppose maximum ratio combining is used to detect the uplink data. The effective uplink signal-to-interference-and-noise-ratio (SINR) is

![]()

where ![]() is the number of antennas. For any given MSE value, it now matters how it was generated, because the SINR is a decreasing function of

is the number of antennas. For any given MSE value, it now matters how it was generated, because the SINR is a decreasing function of ![]() . The term

. The term ![]() is due to pilot contamination (it is often called coherent interference) and is proportional to the interference power

is due to pilot contamination (it is often called coherent interference) and is proportional to the interference power ![]() . When the number of antennas is large, it is far better to have more noise during the pilot transmission than more interference!

. When the number of antennas is large, it is far better to have more noise during the pilot transmission than more interference!

Implications

Since the MSE cannot separate noise from interference, we should not try to measure the effectiveness of a “pilot decontamination” algorithm by considering the MSE. An algorithm that achieves a low MSE can potentially be mitigating the noise, leaving the interference unaffected. If that is the case, the pilot contamination term ![]() will remain. The MSE has been used far too often when evaluating pilot decontamination algorithms, and a few papers (I found three while writing this post) did only consider the MSE, which opens the door for questioning their conclusions.

will remain. The MSE has been used far too often when evaluating pilot decontamination algorithms, and a few papers (I found three while writing this post) did only consider the MSE, which opens the door for questioning their conclusions.

The right methodology is to compute the SINR (or some other performance indicator in the data phase) with the proposed pilot decontamination algorithm and with competing algorithms. In that case, we can be sure that the full impact of the pilot contamination is taken into account.

I wrote

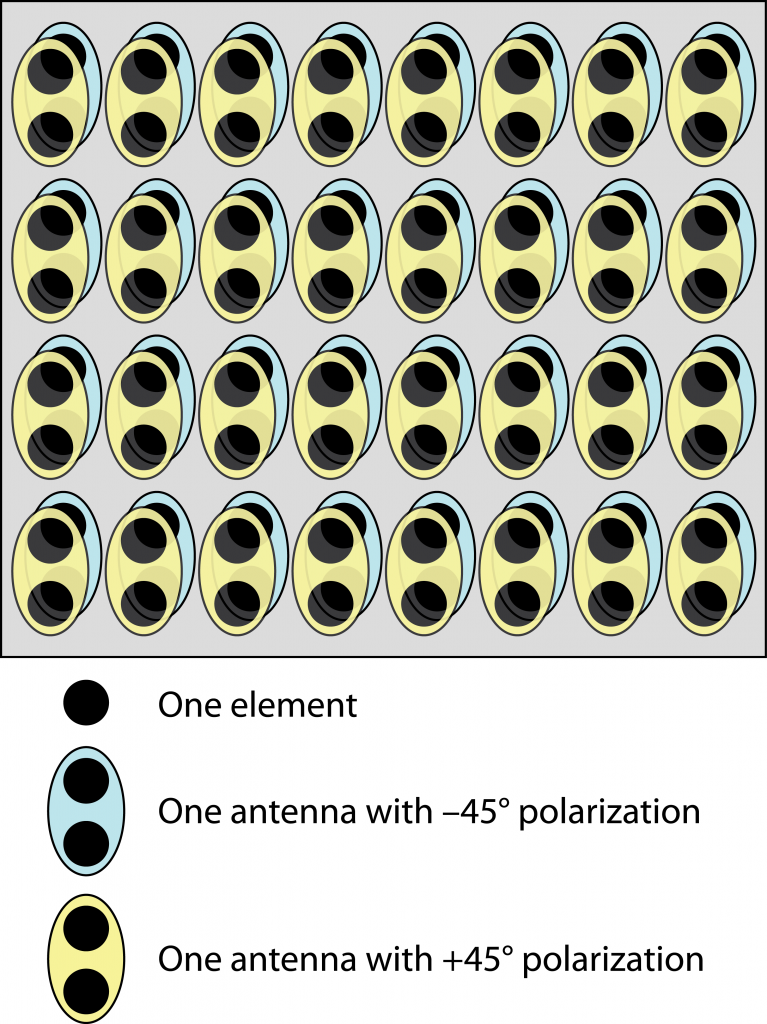

I wrote  So how are the 128 elements mapped to 64 antennas (RF chains)? This is done by taking

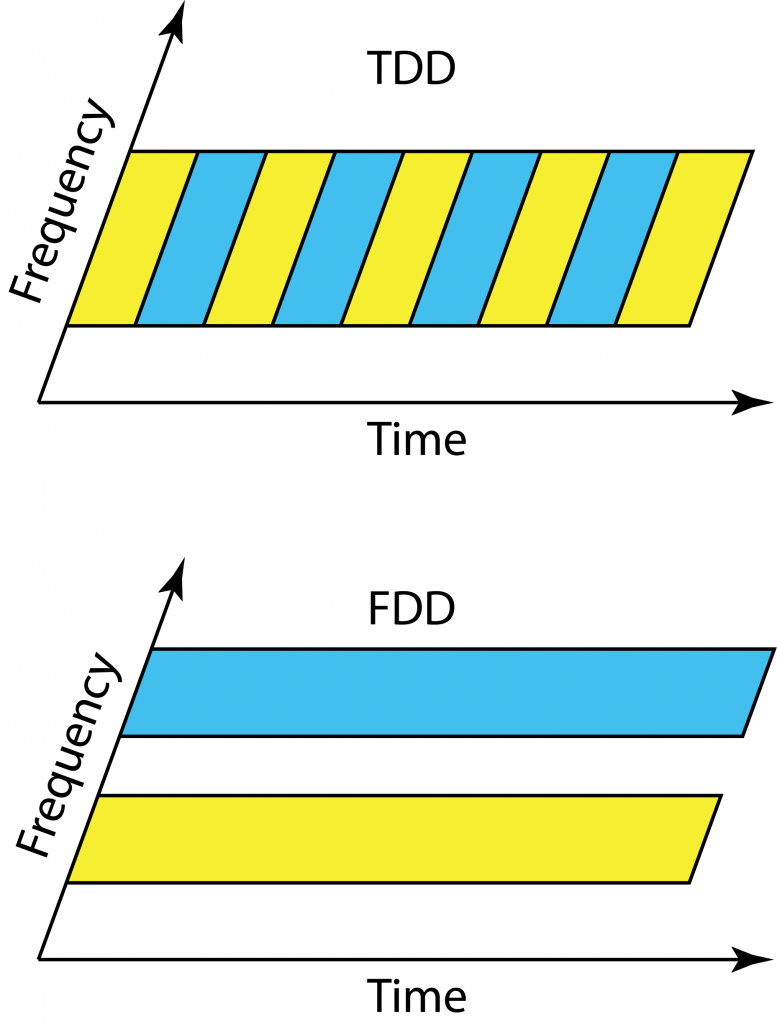

So how are the 128 elements mapped to 64 antennas (RF chains)? This is done by taking  LTE was designed to work equally well in

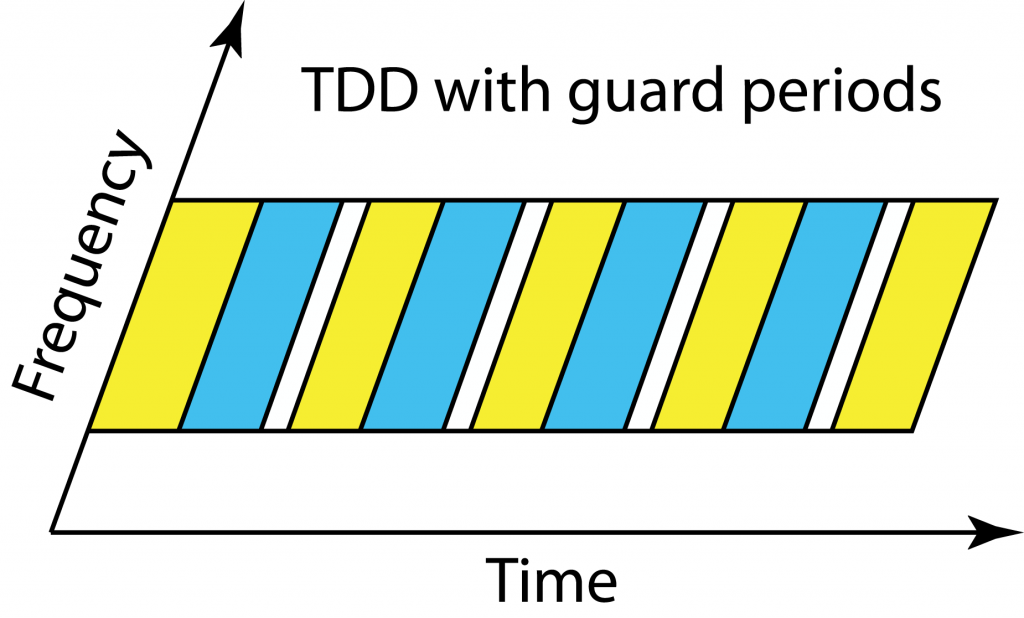

LTE was designed to work equally well in  Everyone in the cell should operate in uplink and downlink mode at the same time in TDD. Since the users are at different distances from the base station and have different delay spreads, they will receive the end of the downlink transmission block at different time instances. If a cell center user starts to transmit in the uplink immediately after receiving the full downlink block, then users at the cell edge will receive a combination of the delayed downlink transmission and the cell center users’ uplink transmissions. To avoid such uplink-downlink interference, there is a guard period in TDD so that all users wait with uplink transmission until the outmost users are done with the downlink.

Everyone in the cell should operate in uplink and downlink mode at the same time in TDD. Since the users are at different distances from the base station and have different delay spreads, they will receive the end of the downlink transmission block at different time instances. If a cell center user starts to transmit in the uplink immediately after receiving the full downlink block, then users at the cell edge will receive a combination of the delayed downlink transmission and the cell center users’ uplink transmissions. To avoid such uplink-downlink interference, there is a guard period in TDD so that all users wait with uplink transmission until the outmost users are done with the downlink.